Hi All!

To illustrate this lesson, I’ll use the song ‘9 crimes’ which features a piano riff of 2 measures (8, 4th-note beats) that starts at the very beginning of the song, and except for very minor variations on the first chord (which wel’ll see in a sec is Amadd9) continues in exactly the same way, all the way through the entire song.

The pop-term for a sequence of music, whether a beat, guitar riff, bass-line or –like in this case- a piano riff, that repeats after a certain amount of time (often not more than two measures) is called a ‘loop’.

The ease of this song is partially in the fact that, since we’re going to play a loop that lasts throughout the whole song, we only have to learn a very short piece of music to be able to play a whole song!

First, listen to the song a bit. You hear a lot of different notes played, very confusing right? Hard to remember? Well, let me teach you a trick and show you –once again- how pop music is ‘built’ with chords and how convenient it is to use the knowledge of chord structures to learn (or even write, ‘cause: yes, our dear friend Damien was also thinking ‘chords’ when creating this haunting piano piece) and especially REMEMBER any seemingly hard to remember song.

Chord structure.

As all of you probably heard me saying one or more times by now, and as I extensively discuss in the course, Pop-Piano is ‘built’ with chords.

Using your knowledge of chords and their structure in your approach to music, can greatly simplify the way you learn.

Let me clarify this fact shortly:

Every piece of music consists of a melody with an underlying harmony to support it, whether the harmony is actually there or not. ‘Not’?

Well, think of a-capella, i.e. ‘solo’ singing for instance, where somebody is just singing a melody by themselves. There is no actual harmony, just the melody that is sung, BUT, the melody does imply a certain harmony, meaning either: 1. although you don’t hear it, your mind ‘fills in the harmonic gap’ and you do imagine the harmony in your head, or 2. when someone would start playing some nice chords, this would ‘fit in’ right away.

The reason melodies imply certain harmonies, is because of the fact that melody notes, are often derived from the harmony and are often also chord notes (or notes from the scale of the key of the song ‘in between’ the chord notes i.e. chord extensions).

This works both ways in the construction of pop-music: Either when a song is written, the harmony is played first with some chords and the songwriter comes up with a melody derived from those chords, or, as with the example of a-capella singing, a melody can be ‘harmonized’ by playing chords ‘underneath’ it.

As ‘riffs’ are repeating melodic instrumental phrases, they too are derived from the harmony. Even more, by repeating these seemingly ‘melodic’ phrases on instruments, they start to imply, construct and become the harmony.

For these melodic phrases are nothing more than single notes derived from the chords, when played in repeated succesion they start to actually form the harmony they’re derived from. These ‘broken’ chords are just chords played with a pattern in which not all notes are played at once, but in succesion.

Using a (broken) pattern in combination with the right chords, is what makes a nice piece on your instrument.

Now try and look at the song and see how difficult you find it after that story, when I tell you that this whole song is played using the very basic ‘broken’ pattern: “down-up”.

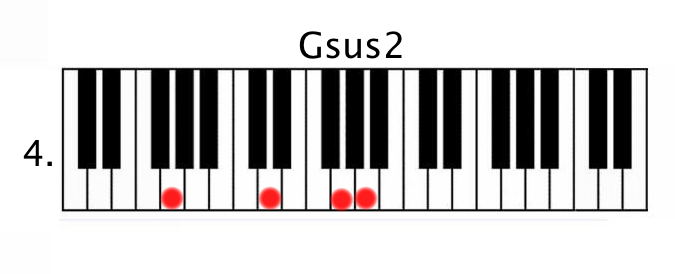

Using a 1,5 technique with the left hand (left hand plays the ‘1’ (root) and the ‘5’ of each chord) and using the voicings (with extensions) as indicated with your right hand.

For Am(add9) the right hand sometimes plays the 2 (=9) and 3, sometimes the 1 and 2. The song starts with a succesion of 1, 2 and 3.

For F the 1 and 2 of the chord are played with the right hand

For the C chord the 1 and the 3 (‘c’ and ‘e’) are played with the right hand.

For the G chord, also the 1 and 2 are played with the right hand.

To play the pattern, start at the lowest note of the voicing in your left hand (the root note on all chords), and ‘walk’ all the way up to the highest note of the voicing in your right hand. In other words: play the notes of each chord in succesion (after one another) constantly starting at the lowes note in the voicing and ending with the highest note of the voicing.

Try to look at what you play and ‘see’ (understand) that you are indeed playing the chords Am, F, C, G (although not the whole triad with your right hand) with an extension here and there.

Easy, right? Not? Learn and practice your chords and patterns!

Questions? Remarks? Show me how you play this song! Please leave a comment below!

I’m also very curious which tutorial you’d like to see next!

All skills, tricks, tips, techniques and knowledge from this- and all other lessons @ this website are taken and can be learnt from my book / course ‘Hack the Piano‘ – The unconventional shortcut method to truly understand music and the piano.

2 thoughts on “Using chords to see and simplify note relations.”

I see no pictures? Is this the same for everyone else?

Problem solved! Thanks Craig.

Comments are closed.